Parallelism

Today’s CPUs support executing code in parallel in three distinctive ways. The C/C++ standards traditionally lack behind in providing standardized support, making most of it unnecessary difficult.

Superscalar computations

Easy for the programmer but most difficult for any computer modern CPUs try to automatically parallelize code by identifying sequential but independent calculations.

c = a + b

d = a + b // can be parallelized

c = a + b

d = a + c // cannot be parallelized

Compilers can optimize code for superscalar execution by interweaving independent calculations. Optimizations for superscalar execution are rarely done manually but it is useful to be aware of the feature if only to understand the output of a profiler which might report more than one calculation per clock due to automatically parallelized execution.

SIMD Instructions

Explicit parallel computation instruction apply basic arithmetic to multiple values at once. Most typically SIMD instructions work on four 32 bit floating point values. This is especially useful for vector and matrix math as it is used frequently in 3D games.

x86 CPUs support floating point SIMD instructions since 1999 using the SSE instruction set extensions. The first implementations worked on 128 bit registers, supporting four 32 bit floating point values. Newer extensions (AVX) support 256 bit registers. On most 64 bit operating systems SSE instructions are used exclusively for floating point calculations in 64 bit applications, abandoning the older FPU instructions.

ARM CPUs support a similar instruction set extension called NEON, which is optionally supported starting with Cortex-A8 CPUs.

C/C++ does not provide platform agnostic SIMD support. Instead compilers add CPU specific intrinsic functions that map directly to CPU instructions. SIMD programming in C/C++ is therefore basically like assembler programming, but register numbers are handled automatically.

#include <xmmintrin.h>

__m128 value1 = _mm_set_ps(1, 2, 3, 4);

__m128 value2 = _mm_set_ps(5, 6, 7, 8);

__m128 added = _mm_add_ps(value1, value2);

float allAdded = added.m128_f32[0] + added.m128_f32[1]

+ added.m128_f32[2] + added.m128_f32[3];

SSE or NEON code is generally portable across compilers but SSE and NEON code is incompatible.

Multithreading

Multithreading is directly supported in C and C++ since 2011. As operating systems started supporting (preemptive) multithreading before 2011 every operating system provides a distinct set of APIs. Professional games traditionally avoided multithreading until it became necessary to use all resources provided by multicore CPUs. Multi CPU game systems have been around since the 80s but have always been rare exceptions. But now just about every CPU includes multiple CPU cores.

Preemptive (aka real) multithreading runs multiple execution threads completely independent but in the same address space. Using the shared address space the same data can trivially be used from multiple threads, but working on the same data can lead to lots of very hard to debug problems – most notably race conditions.

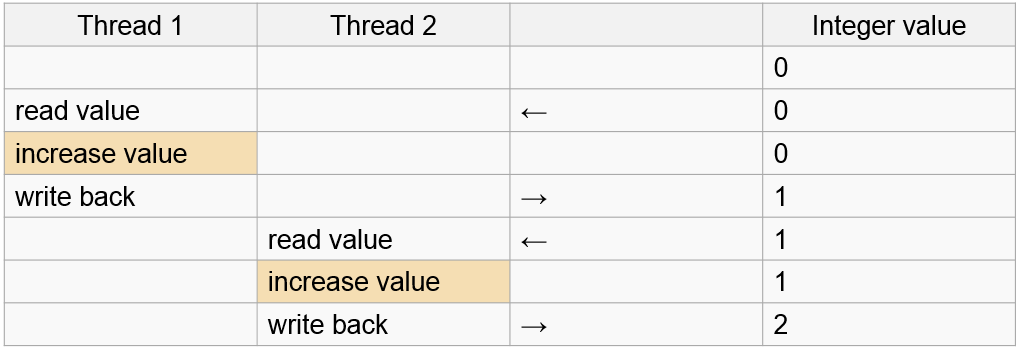

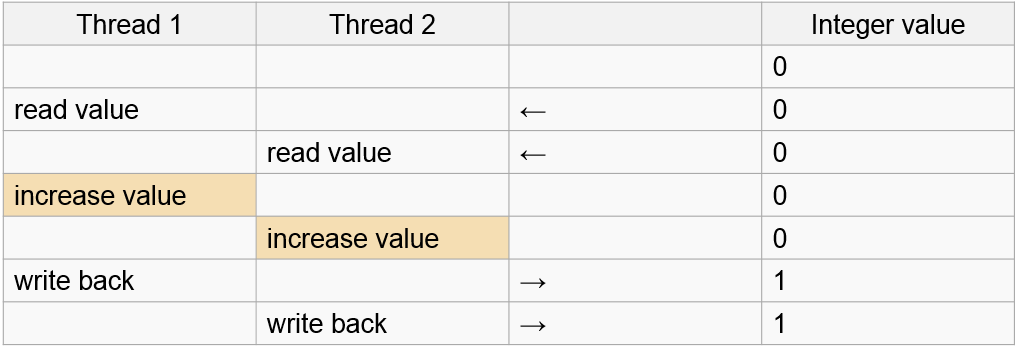

Changing the same value from different threads can work out nicely.

But it can also fail in obscure ways.

Race conditions are especially nasty because they might happen very rarely and seemingly at random.

Threading apis provide synchronization primitives, usually called mutexes to synchronize data access. A mutex can be locked and while a mutex is locked in one thread every other thread that tries to obtain a lock has to wait for the other thread to unlock the mutex. Using mutex locks data can be protected from unordered access, but using locks frequently can slow a program down considerably. Data synchronization in multithreaded programs should be well thought out to minimize synchronization points. Typical designs for multithreaded game engines assign complete subsystems like for example the physics system to a single thread and only synchronize all subsystems once per frame. More sophisticated systems, which scale better to larger numbers of CPU cores use job systems – a worker thread manages a list of jobs and assigns them to different threads. Typically the worker thread also explicitly handles synchronization points.

It is also possible to synchronize data without using locks. CPUs provide atomic operations which are guaranteed to modify memory locations atomically. Lock free programming however is a difficult task reserved for only the bravest of the programmers.