CPU Internals

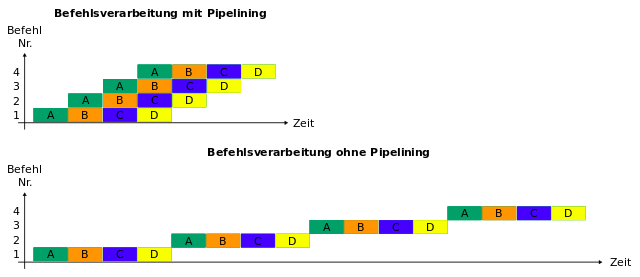

Modern CPU cores use a decreasing amount of their transistor count for actual instruction based computations. As more and more ALUs (arithmetic logic units) are added it becomes increasingly difficult to keep these units busy based on a single thread of instructions. Pipelined execution is the norm since many years which divides every instruction in simple, discrete steps to increase parallelism because the first step of the following instruction can be executed while the previous instruction’s second step is worked on.

Pipelined execution, especially when combined with multiple ALUs, can lead to three basic kinds of hazards which slow down execution.

Structural Hazards

A structural hazard happens when the CPU does not contain sufficient hardware to execute all calculation steps which could be scheduled for the current step in parallel. This kind of hazard is mostly not a problem for the program as it usually means the CPU is working at or close to its full capacity and CPUs spend more and more hardware to prevent structural hazards.

Data Hazards

Data hazards happen when a calculation depends on the result of a previous calculation which is not yet finished due to the pipelined execution. Data hazards are an increasingly bigger problem for CPUs which can do more and more work in parallel.

Some data hazards can happen purely because of register name clashes.

subl rcx, rax

addl rbx, rax

Here the register rax is written two by two successive instructions but the calculations themselves are independent of each other. In these cases CPUs can temporarily rename the used registers because they internally contain more registers than can be addressed directly.

Real calculation dependencies however cannot be avoided that easily but instructions can be reordered to intertwine independent calculations. This can be done by the compiler but more and more modern CPUs can reorder instructions themselves while they are executed. Helping out manually to avoid data hazards is increasingly difficult.

Control Hazards

As many instructions are in work in parallel dynamic branching can slow down execution significantly because the pipeline has be flushed when the CPU cannot determine where exactly instruction execution continues. This is called a control hazard. CPUs try to avoid them by continuing execution at some speculative address. When this fails all speculatively executed instructions have to be reverted. The speculation algorithms become more powerful with each new CPU generation but there has to be some pattern in the branching for speculative branching to work effectively. For that reason sorting data which is used to calculate dynamic branches later can greatly speed up execution.

Memory Access

In most programs memory access is much more critical for performance than the pure execution speed of the CPU. Today’s computers use a cache hierarchy to speed up memory access which usually looks approximately like

L1 cache ~ KiloBytes L2 cache ~ MegaBytes Main memory ~ GigaBytes

L1 cache ~ 0.5 ns L2 cache ~ 7 ns Main memory ~ 100 ns

Main memory is very slow compared to the speed of modern CPUs which could calculate hundreds of instructions while waiting for a single memory access. Similar to branch predictions CPUs try to predict which data is used next and preload the data into the L2 or L1 cache. This also works best when regular access patterns are used – for example when the same data is used over and over or when large blocks of memory are read sequentially. Because of the large discrepancy of CPU and memory speeds regular memory access patterns are critical for performance.

Memory is read by the CPU in blocks of constant sizes, called cache lines. Cache lines are usually about 64 bytes in size (modern intel CPUs use 128 bytes) and regarding the size of the cache lines can potentially further increase performance. Thankfully C/C++ makes the actual use and structure of data in memory more transparent than most languages, especially when plain C structs are used, avoiding object oriented features like constructors and virtual member functions. Those plain structs are often called POD (plain old data) structs.

struct Data {

int a;

float b;

};

A plain array (aka Data data[64];) is always just a contiguous amount of memory of the size 64 * sizeof(Data).

Memory can also be explicitly aligned in C++ 11 using the alignas construct to use the cachelines more effectively.

struct alignas(16) Data {

int a;

float b;

};

alignas(128) char cacheline[128];

Older compilers and operating systems usually provide built in extensions and functions for data alignment, too.